The Arnolfini Portrait, as the title states, was revolutionary in its time and fascinates to this day. The double portrait is not in the category of simple representational art. Instead, everything in the picture attracts the viewer’s attention to details which could be an important message or convey a meaning.

Jan van Eyck ranked among the most respected Flemish painters, active in the first half of the 15th century. His name is connected with an early school of Netherlandish painting, and his work is also representative of the art of the Northern Renaissance.

Van Eyck was a painter of both religious and secular pictures.

Jan van Eyck – Arnolfini Portrait, 1434

One from the second category is The Arnolfini Portrait, dating from 1434. The picture is hanging in London National Gallery and most likely portrays Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his wife Costanza Trenta. The couple’s identity was narrowed down from only a few other possibilities, but only they lived in Bruges long enough to get to know the painter closely.

The first key to the painting is the setting, in a fairly wealthy household, filled with beautiful and rich objects and clothing.

The symbols in the painting are impossible to overlook, although they are not of a single interpretation. Neither is the meaning of the picture completely clear.

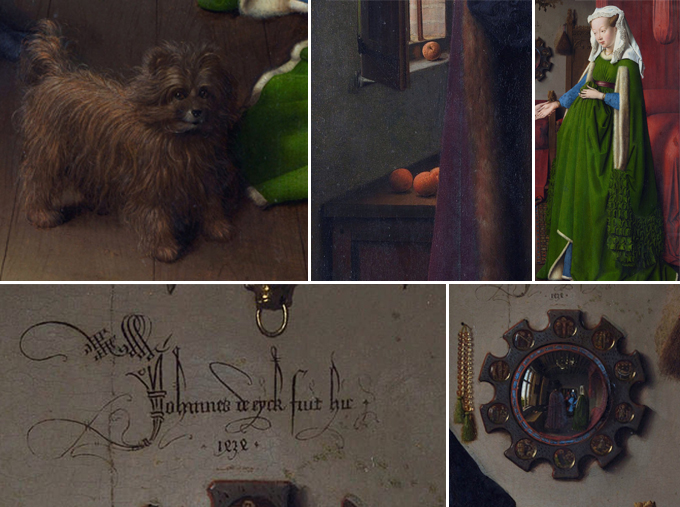

Details interpreted as symbols of a wedding event

Over the centuries it has been interpreted as a portrait of a newly-wed couple, with symbols drawn from a wedding event, starting with the obvious fertility symbol of the pregnant-like position of Constanza’s body, which as shown was just a fashion caprice. In fact, the couple was ultimately childless.

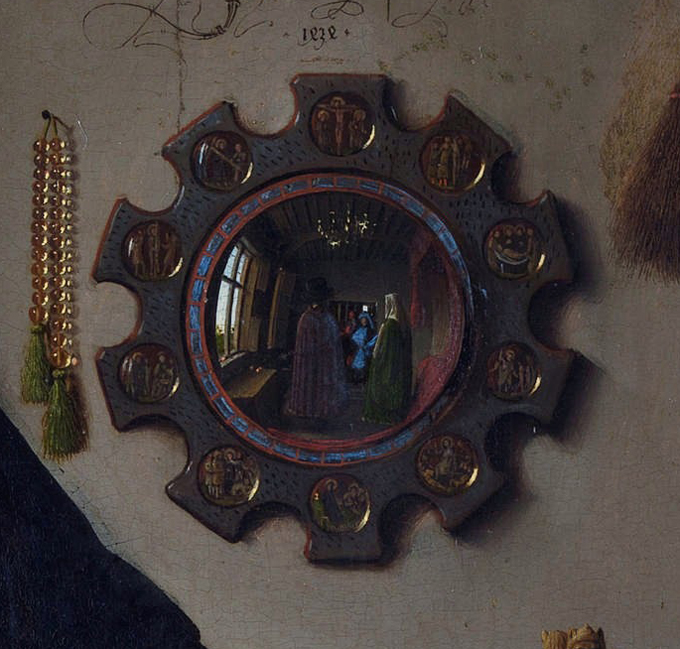

Other fertility symbols are the red bed and carpet. The shoes lying on the wood floor also had meaning as common wedding gifts to a bride from a groom. The oranges symbolise fertility and love, the little dog loyalty. Finally there is the remote mirror reflecting two extra people, one of them supposedly Jan van Eyck, who also added his signature above the mirror and a quote: “Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434” (Jan van Eyck was here, 1434). That should serve as legal documentation of a marriage contract, with the author acting as a witness to the wedding.

Headdress was typical for a married woman

Margaret D. Carroll, on the other hand, suggests in her Journal article “In the Name of God and Profit: Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait“, published by the University of California Press,that the couple is already married, since the hair of Constanza is not down as it would be for a bride, but is hidden under a headdress, as would be typical for a married woman in those days.

She also points out that the wedding would have taken place in a church with a priest, not in the privacy of a house and without relatives. She instead suggests that the purpose of the painting could have been to document at Giovanni’s granting legal authority to his wife. Such an occasion would be appropriate in a domestic surrounding, presenting a witness and notarial authority.

The most important part of the painting, though, which is not shown, is the discrepancy in the years. The painting, as mentioned above, was dated in 1434, while Costanza Trenta died in 1433.

The painting could also have had a different context from the one under which it was finished. As an x-ray has shown, Jan van Eyck did make several changes, and whether those were related to such an occurence or not is subject to dispute.

Margaret L. Koster offers another explanation in her “The Arnolfini Double Portrait: a Simple Solution“. According to her, the painting could have been a memorial picture. The very same symbols from above would, in this circumstance, have a contrary connotation.

According to Margaret L. Koster, the faces of the couple are contrastingly depicted

She starts with the contrasting depiction of the couple – while Giovanni looks realistic, Constanza is more of an idealisation. This could mean that they were separated by death. Margaret L. Koster also invites attention to the melancholic look in Giovanni‘s face.

The decorations of the mirror frame – left side narrates a life of Christ, while the right side his death.

The picture is optically divided into a left and right part by many symbols (from the viewer’s point of view). The mirror, for instance, and the decorations on the left side of the frame are dedicated to the life of Christ, while the right side to his death.

But this is not all. Constanza is wearing bright green and blue – symbols of love and faithfulness. Giovanni, in contrast, wears darker colours – not yet black, which became standard mourning attire much later, in Victorian times.

Dog by the woman´s feet was a symbol on women’s tombs

Even the dog can be a symbol of death considering the common use, in the middle ages, of carvings of dog on women’s tombs.

Candle above Giovanni is light up, candle above Constanze is burned out

And finally, the chandelier has one candle light above Giovanni, even though this is a day time scene. There is no candle light above the head of Constanza. In fact, there is a burned-out candle in the holder above her. This clearly cannot be a coincidence since Jan van Eyck would not have painted the picture without a special meaning, Koster believes.

From the work of Margaret L. Koster it emerges that the painting was more likely a husband’s hommage to his deceased wife than a memorial to an important person in his life.

Photo: Flickr – cea +

Photo editing for the purpose of this article: Martina Advaney

Support us!

All your donations will be used to pay the magazine’s journalists and to support the ongoing costs of maintaining the site.

Share this post

Interested in co-operating with us?

We are open to co-operation from writers and businesses alike. You can reach us on our email at [email protected]/[email protected] and we will get back to you as quick as we can.