When it comes to Albrecht Dürer, most will surely remember at least one of his works. His self-portrait, significantly reminding the viewer of Jesus, is one of the paintings that art books like to reproduce. Similarly it is with the famous engraving, Adam and Eve, from 1504, or the detailed depiction of a rabbit in watercolour – Young Hare – from 1502. In 1514, however, Dürer created a copperplate titled Melencolia I, which was immediately understood to be a masterpiece.

Albrecht Dürer – Self-Portrait at 28 (1500), By Fooh2017 – Own work, CC0, Link

Adam and Eve (1504) By Albrecht Dürer – themorgan.org, Public Domain, Link

Albrecht Dürer was an active painter and printmaker during the German Renaissance, of Hungarian origins. His father was a succesful goldsmith, and his godfather was a publisher who owned several workshops. That helped Dürer to master both mediums from an early age. Nevertheless, as he himself claimed, he always preferred painting to goldsmithing.

Undoubted benefits also came with his marriage to Agnes Frey, who came from a prominent family in Nuremberg.

Albrecht Duerer House, Nuremberg, Germany / Photo: Shutterstock

Over the course of his life, Dürer made several journeys abroad, partly to escape from the plagues that broke out in Nurenberg time and again. The visits abroad also contributed to establishing his reputation in Italy and the Netherlands; and needless to say, both countries had an impact on his work. Already a respected painter, he had a stroke of good luck when he was invited to the court of Maxmilian I, who became his patron and promised him a life annuity. Even though this status became doubtful when the Habsburg ruler passed away, by the time Dürer died, he left this world as a rich man, leaving a respectable property to his family.

By Albrecht Dürer – _AGDdr3EHmNGyA at Google Cultural Institute, zoom level maximum, Public Domain, Link

Melancholia I is full of obviously meaningful objects which have been analyzed many times without a conclusive result. And the fact that the painter himself offered no hints adds to the mystery.

The print depicts an angel in an melancholic state, holding a compass in one hand and supporting his head with the other hand, surrounded with many symbolic objects and scenes.

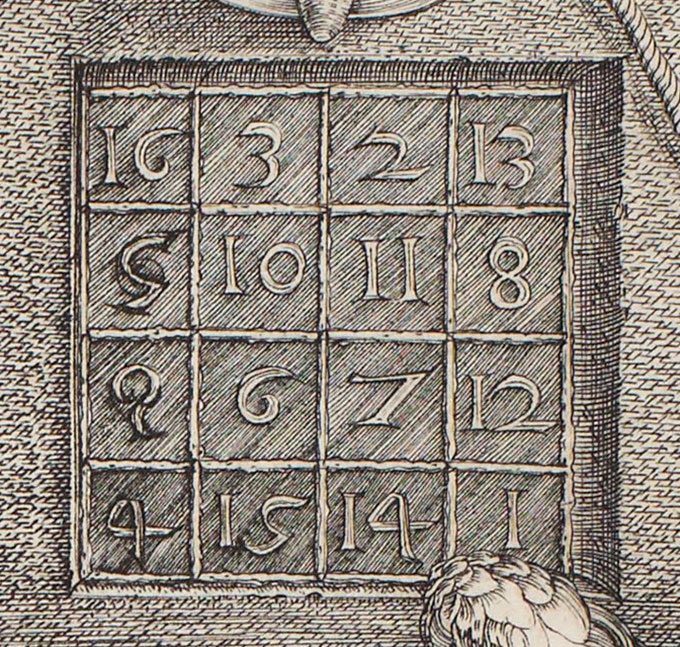

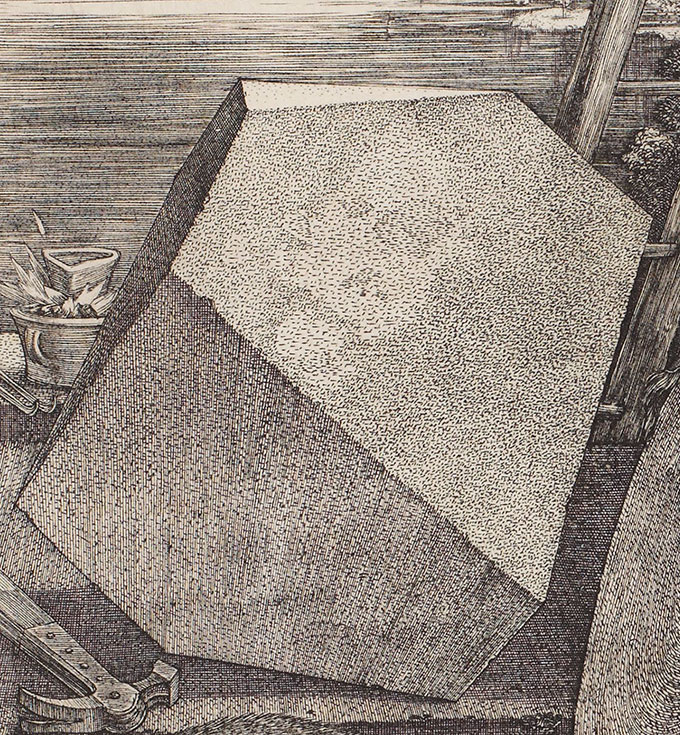

From the apparently disorganised tangle of scientic objects in the print, two stand out: a Numeral Square – called the Magical Square – behind the figure of the angel and the mysterious polyhedron which occupies a good part of the left side of the print.

Magical Square / Photo: Wikipedia / Editing for the purpose of this article: Martina Advaney

The Magic Square – referring to the numerological object in the upper part of the print – gives the same result counting the digits in any direction – horizontally, vertically, diagonally, and also within all the quadrants. The result is always 34, which further adds up to 7 (3 + 4). When you count the number of segments comprising the square, even then the result is 7 (there are 16 squares, which works out to 1 + 6 = 7).

Number 7 can have several meanings linked to numerology, astronomy, astrology, math…

What is certain is that there are two digits in the middle bottom line, 15 and 14, that relate to the year Dürer created Melancholia I.

The polyhedron is the other unexplained item which triggers further questions.

Polyhedron / Photo: Wikipedia / Editing for the purpose of this article: Martina Advaney

Dr. Ernst Theodor Mayer, a former psychiatrist from Munich, believes that by projecting the apexes of the polyhedron vertically, they form a Star of David, while projecting them horizontally, they perfectly fit into Magical Square, as seen here. So are these two items connected?

According to another theory, the polyhedra could be pointing towards the crystal. The question remains, whether that was technically Dürer´s aim.

And of course there are other things that remain unresolved. Could the depiction serve as Dürer´s inner statement, or is it more generic?

The National Gallery of Art in Washington suggests that the print represents the limits of human knowledge, while being surrounded with the objects from the various fields of study that were known during the artist´s lifetime.

Irrespective of the real meaning of the engraving called Melancholia, the technical aspect alone ranks Melancholia I among the real gems of art history. The execution of the print, with the finest details providing its plasticity, is truly amazing.

Support us!

All your donations will be used to pay the magazine’s journalists and to support the ongoing costs of maintaining the site.

Share this post

Interested in co-operating with us?

We are open to co-operation from writers and businesses alike. You can reach us on our email at [email protected]/[email protected] and we will get back to you as quick as we can.