In Part One of this interview, we spoke to Professor James Danckert, an eminent cognitive neuroscientist discuss boredom in life and the workspace and the health problems that can lead to. James also tells us more about his work with mental models and the brain and how he nearly became a fiction writer.

Professor Danckert, before we get onto boredom, you have said you first wanted to become a fiction writer but became a neuroscientist. How?

I took Literature and Psychology as a double major in undergrad and at about second year I became enthralled by the brain. It was also obvious at that point that my skills as a fiction writer were not competitive with my peers.

There were other ‘sliding door’ moments – in general I say yes to opportunities as they arise and this led me to where I am now.

What is boredom?

Boredom is the uncomfortable feeling of an unmet desire to be engaged in something meaningful.

When we’re bored we want something to do, we just don’t want any of the options that are currently available to us.

So it comes packaged with a sense of agitation and restlessness which sets is well apart from apathy or laziness which does not have any motivation to engage.

What are its links to brain injury?

People who have suffered traumatic brain injury (TBI) report experiencing boredom more post-injury.

This was an anecdotal claim until a few years ago when we published work with a large group of people who had no brain injury, 340 people who had suffered mild TBI (usually a concussion of some sort) and 35 people who had suffered moderate to severe brain injuries.

We showed that having had a brain injury was predictive of your level of boredom proneness.

So for some reason (and more research is needed) their brain injury made it more difficult for them to engage with the world around them and boredom became a prominent experience as a result.

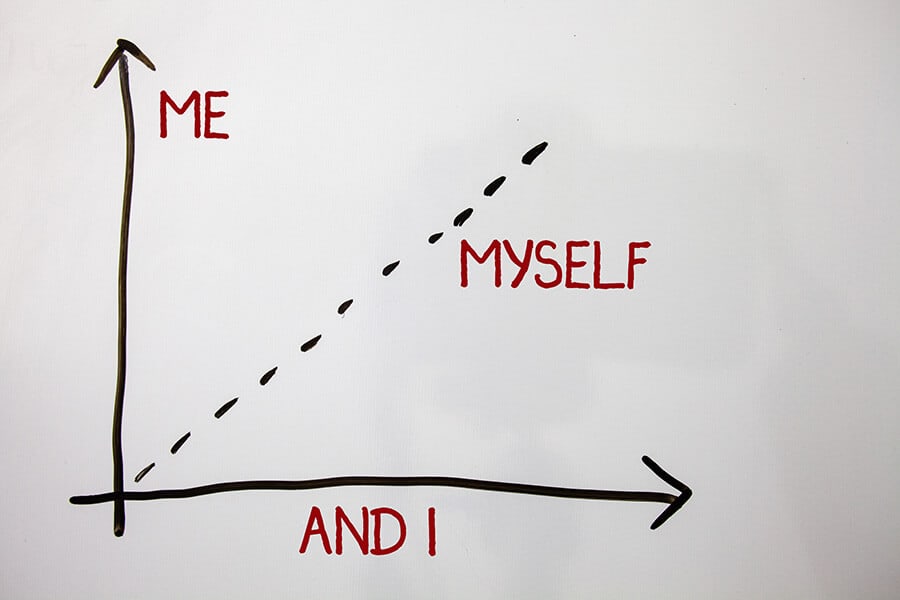

Big Egos

What are its links to the ego of an individual? Do egocentrics become bored more easily?

We don’t know the relation to ego-centrism and boredom. We do know that boredom proneness is positively correlated with narcissism – but a specific form of narcissism.

So an overt narcissist – someone who is constantly bragging about how wonderful they are (think Donald Trump) does not experience boredom much.

But a covert narcissist – someone who feels that the world is failing to see or acknowledge their talents – does experience boredom a lot.

It seems that the sense that they big life goals have failed (not through their fault but the failure of others) has made them boredom prone.

What makes a boring person?

Again, narcissism (this time overt) may be important. If you fail to listen to the stories of others you risk being seen as boring – but that’s speculative at this point.

It has been said that risk taking is linked to testosterone. Do those who are prone to taking risks have a tendency to quickly get bored?

Boredom proneness is associated with self-reported impulsivity and increased risk taking. It has also been positively associated with sensation seeking.

But these relations are all based on self-report. We don’t have good evidence that there are consequences for cognitive control in laboratory based tasks. So there is more work to be done there.

Keeping The Spark

Do a fair percentage of couples get bored with each other after having spent a few years together?

There is such a thing as relational boredom and sexual boredom in which partners become bored with one another.

It is not necessarily about the number of years spent together (although that may contribute) – it’s more likely about the need to balance two things in a relationship – security and growth.

The former might promote doing familiar things which could lead to boredom. But too much of the latter (constantly looking for new activities to do) could lead to destruction of the relationship.

So we seek a balance between them and boredom in the relationship might signal that we aren’t achieving that balance.

It has been reported that many couples have had a falling out during the last one year due to being locked in together on account of Covid. On the other hand would it be fair to assume that some percentage of couples would have grown closer within the same scenario?

It is entirely possible that many couples have grown closer. Perhaps using the lockdown as a time to reflect on what matters in our lives can allow couples to reinvigorate their relationships. But we don’t have great data on that.

Inherited Boredom

Does boredom also have a link to the genes we may have inherited?

We are in the process of examining this. We started by looking at the human orthologue of the so-called foraging gene.

We started there because foraging is a self-regulatory behaviour highlighting the need to balance the twin drives of exploration (seek resources you need) and exploitation (use those resources to satisfy drives).

Boredom can be seen as a self-regulatory signal prompting a phase of exploratory behaviour.

We’ll also be looking at genes that regulate the neurotransmitter Dopamine which is important for evaluating reward and value. But we do not have the data in yet.

Jobs and Boredom

A vast majority of people are engaged in jobs for the sake of earning a living. Few have the good fortune to be in a profession that may also be a source of pleasure for them. What are the risks of boredom and burnout for such individuals and what would be your recommendations?

A study from 2011 by Britton and Shipley of civil servants in the UK showed that people who reported being bored at their job more often were also more likely to die from heart disease later in life.

It’s important to note that this is correlational and there are potentially lots of other factors to consider (e.g., are sedentary jobs – which are not good for heart health – also more likely to be boring?).

But long term chronic boredom is not likely to be good for our mental health. We know that being boredom prone is associated with higher rates of depression and anxiety and higher use of drugs and alcohol.

So if we fail to respond well to boredom the outcomes are generally not positive. Also, we showed that inducing boredom temporarily raised people’s cortisol levels. Chronic elevation of this stress hormone is also unlikely to be good for our physical and mental health.

Are those who are genuinely mindful and meditative, less prone to boredom?

Yes – practicing mindfulness meditation successfully will generally lead to less boredom in your life.

The challenge is in asking people who are already prone to boredom and who struggle with focusing and sustaining attention, to engage in a practice that requires focused and sustained attention.

It’s a little like asking a drowning person to swim ashore – they would if they could.

That’s the conundrum of boredom – the recognition of a desire to be engaged, coupled with the failure to launch into anything that will adaptively satisfy that desire.

Photos: From the Archive of Professor James Danckert; Shutterstock

Part Two of this interview will appear next week. For now, here is another intriguing interview for you:

Support us!

All your donations will be used to pay the magazine’s journalists and to support the ongoing costs of maintaining the site.

Share this post

Interested in co-operating with us?

We are open to co-operation from writers and businesses alike. You can reach us on our email at [email protected]/[email protected] and we will get back to you as quick as we can.