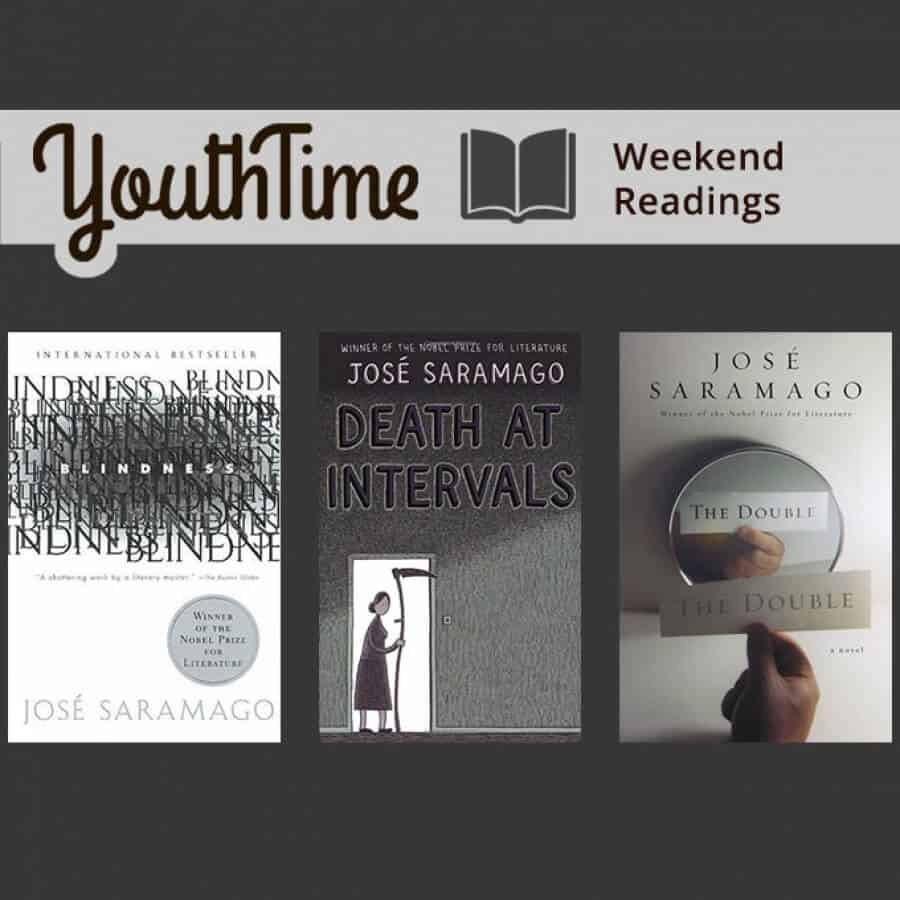

José Saramago was a Nobel Prize-winning Portuguese writer, a late bloomer – as many said about him. He published his first novel when he was 25 years old and then took a long break from writing. Later, he became a prolific novelist who published a new novel every year or every other year. His life path was quite interesting: he worked as a car mechanic after graduating from a technical school, then worked as a translator and a journalist, and finally – found his place as a writer. His numerous works offer readers diverse stories, but this time – we will recommend three of his novels that have storylines with surreal elements or that are great allegories that depict dystopian worlds: Blindness, The Double and Death with Interruptions.

The first-mentioned novel, Blindness – gradually develops a disturbing storyline that will seem horrifying at several climax points. In Blindness, a sudden and unexplainable epidemic of blindness breaks out. It starts with a man who is driving his car: at a traffic light, he loses his sight completely and creates a traffic jam, helplessly shouting: I am blind! A man who volunteers to guide him home ends up stealing his car. But, then – he becomes blind, too. The epidemic spreads rapidly, without any detectable cause. This causes mass panic, which leads the government to take extreme measures. All those who are blind must be isolated in an asylum, in order to control the epidemic. New circumstances progressively create a disturbing, dystopian world. Everyone goes blind, except for one woman who keeps that fact to herself. One would expect that, under these conditions, people would work together, united. The truth is far more disturbing: even without their sight, people are fighting for power, committing crimes, being disrespectful and reckless. The asylum gets more and more crowded, which leads to greater anxiety and hostility among people. Lack of food and bad hygienic conditions make matters worse. The situation is not getting any better, but the characters (above all the woman who miraculously didn’t go blind and her husband, a doctor) discuss the epidemic and deeper questions of humanity:

I don’t think we went blind, I think we are blind, blind but seeing, blind people who can see, but do not see.

As the story unfolds, the reader may interpret the allegory of blindness in several ways, which makes reading this book a sobering experience you won’t be able to forget for a long time.

Saramago’s novel The Double does not have this kind of apocalyptic storyline, although it will give you the chills in a different way. The theme of a double has been frequently used in horror fiction (take Edgar Allan Poe or Lovecraft as good examples) since there is something deeply unsettling in its core. Saramago incorporates this element into the search for identity of the main character, Tertuliano Máximo Afonso. Afonso is an apathetic and depressed high school history teacher who doesn’t seem to find any joy in life anymore. Afonso’s colleague notices his state, so he recommends that Afonso find a way to have fun. He suggests renting a movie. Afonso takes his advice, although he is not too excited about it. The story starts to get interesting when Afonso notices a character in the movie who looks exactly like him. He becomes obsessed with his double and starts investigating the actor’s identity. He finds out the name of the actor is António Claro, and he manages to contact him and convince him to meet, which leads to a surreal twist of events. Wanting to be somebody else or not knowing who he is, has led Afonso to engage in many activities that he didn’t even know he was capable of doing. Being completely identical to Claro, Afonso starts losing his way. But, as the novel says:

It was said that one of them, either the actor or the history teacher, was superfluous in this world, but you weren’t, you weren’t superfluous, there is no duplicate of you to come and replace you at your mother’s side, you were unique, just as every ordinary person is unique, truly unique.

One of the greatest things about this novel is the element of surprise: just when you think the story has reached its climax, another storyline emerges, an unexpected plot twist happens – which will live you breathless.

In the novel titled Death with Interruptions, Saramago explains the importance of dying through an allegory. This may sound a bit morbid, but the novel actually has a special kind of humor that will stick with you for a long time. As in Blindness, in this novel Saramago experiments with all the possible what ifs. We can imagine Saramago sitting in his armchair and thinking to himself: what if death decided to quit her job and nobody died ever again? Exploring this scenario in the novel, Saramago shows us just how pertinent death is and how the circle of life is something magical and incomprehensible. In his own way, Saramago creates yet another dystopian world, where people are at first happy to be given the gift of immortality, but soon come to realize the problems that result, mainly from a demographic and economic perspective. Death declares she is on strike within the borders of one, unnamed country. Overpopulation is a problem that gets more concrete and real as days go by. All this leads to the establishment of an underground group known as the maphia: they help people illegally cross the borders so that they can die. Things start to get interesting when death returns to her job and falls in love with a cellist. Nevertheless, the message is clear:

Whether we like it or not, the one justification for the existence of all religions is death, they need death as much as we need bread to eat.

There is one important thing to understand about Saramago’s approach to writing: his writing style has often been criticized as a bit confusing, similar to the stream of consciousness, although it does not necessarily have any distinctive function in his works (except for in Death with Interruptions). His sentences are a bit long, and he doesn’t use much punctuation. This may be a barrier when you first start reading, but don’t be deterred. Saramago’s style may be unconventional, but once you persevere through the first fifteen or twenty pages, you will get drawn in his beautiful and often unsettling worlds and you will feel entirely at home.

Support us!

All your donations will be used to pay the magazine’s journalists and to support the ongoing costs of maintaining the site.

Share this post

Interested in co-operating with us?

We are open to co-operation from writers and businesses alike. You can reach us on our email at [email protected]/[email protected] and we will get back to you as quick as we can.