When Professor Jordan Peterson from the University of Toronto decided to publish his psychology lectures on Youtube he had no idea how popular they would be.

Within months, lectures on Carl Jung and dozens of other subjects had gained millions of views online. Peterson, a successful clinical psychologist and engaging public speaker, was undoubtedly the star of the show.

After his Youtube success, Peterson decided to set up his own channel. Hundreds of videos cover a range of subjects, from psychological archetypes to cleaning your room.

Today Peterson has almost 600,000 subscribers and his channel has clocked up more than 35 million views.

If one professor can personally reach tens of millions of people in mere months, what does that mean for the university? Students pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in tuition fees. What if Peterson were to offer his entire course online for free?

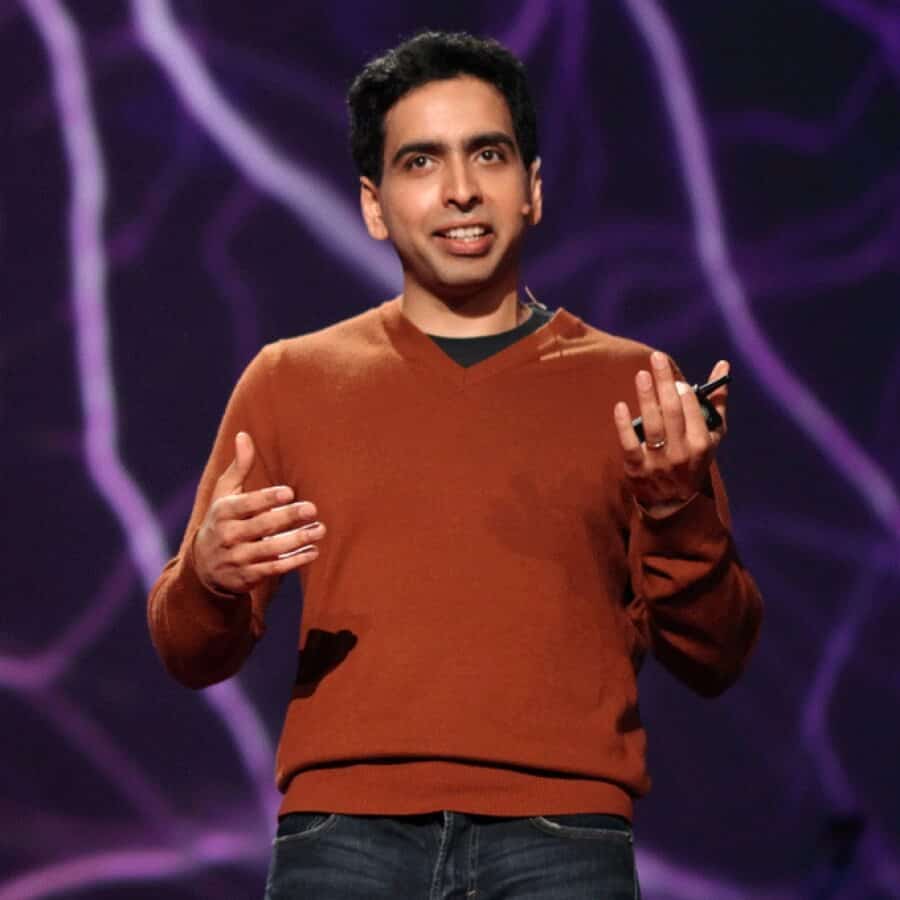

That is not a hypothetical question. Peterson is just one of hundreds of educators worldwide who are pondering the future of the university as an institution. Perhaps the most famous example is Khan Academy. Set up in 2006 by hedge fund analyst Salman Khan, the Academy offers free online lectures on a remarkable range of subjects. An estimated 40 million students watch its videos each month entirely free of charge.

Khan himself studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Another MIT alumni is Anant Agarwal who helped create edX in 2012. With more than 10 million online students, edX offers university standard courses for a fraction of the price charged by most institutions.

Critics who argue that online learning through videos is no substitute for attending lectures in person have been proven wrong. Studies show that students absorb information equally well, if not better, online. Exam results confirm that remote learning works. Students can pause, rewind and rewatch online lectures as many times as they like. They can watch them at times which are more suitable, show them to friends, and discuss the ideas online with their digital classmates.

University of Toronto has 60,000 students compared to Peterson’s 600,000 subscribers.

Photo credit Wikimedia Commons

With technology advancing at such a rapid rate the idea of watching a lecture on Youtube will soon seem old-fashioned. Virtual reality learning could see engineering students building digital bridges in their bedrooms in Beijing, Istanbul and Moscow. So why do universities still exist? The answer is accreditation. Students will pay $10,000 for a degree in psychology, even if all the lectures are freely available on Youtube, because it is an investment in their future.

Meanwhile someone who watches hundreds of geology lectures with Khan Academy will have little chance of being hired as a geologist without a degree. Their level of expertise is almost irrelevant. Studying online will help, but what they need to earn money is a certificate from a reputable university.

Accreditation is where the next big battle lies. Today there are hundreds of competing ideas on how to capitalise on the emerging era of digital learning. There is cause for both optimism and pessimism. Khan Academy’s positive vision of free online learning could come to dominate global education. Under this model, learning platforms would develop testing methods so students could be properly evaluated on their knowledge. Physical exams could be offered, or security technology developed to prevent cheating. The top five percent would achieve a distinctive grade and exams would be hard enough to ensure that only dedicated and capable students pass.

The marketplace would sort out which accreditations were valued by employers and which weren’t. Billions of lives would be transformed by accessible, quality education at an extremely low price. But a negative outcome isn’t far-fetched. Giant tech companies like Google and Facebook are certain to want a piece of what will surely be a lucrative market. Youtube is already owned by Google and, at least in the western world, there isn’t much competition in the social media space. Facebook has already started its own university. What if it offered its billions of members the chance to get a valuable qualification simply by spending even more time online? Facebook could create a paywall and charge $1 to watch a lecture.

In 10 years the world’s elite universities might not be Harvard, Oxford or MIT, but Apple, Facebook and Google. Commercialised education would have little appetite for in-depth learning. Short, snappy and entertaining videos would attempt to cram 5,000 years of knowledge into a five-minute clip.

Predicting the exact landscape of this brave new world is virtually impossible. But it seems clear that the University as a physical institution is almost certainly finished. Digital learning is a revolution that stands alongside the invention of the printing press as a milestone in human history. And we are just at the beginning.

Support us!

All your donations will be used to pay the magazine’s journalists and to support the ongoing costs of maintaining the site.

Share this post

Interested in co-operating with us?

We are open to co-operation from writers and businesses alike. You can reach us on our email at [email protected]/[email protected] and we will get back to you as quick as we can.