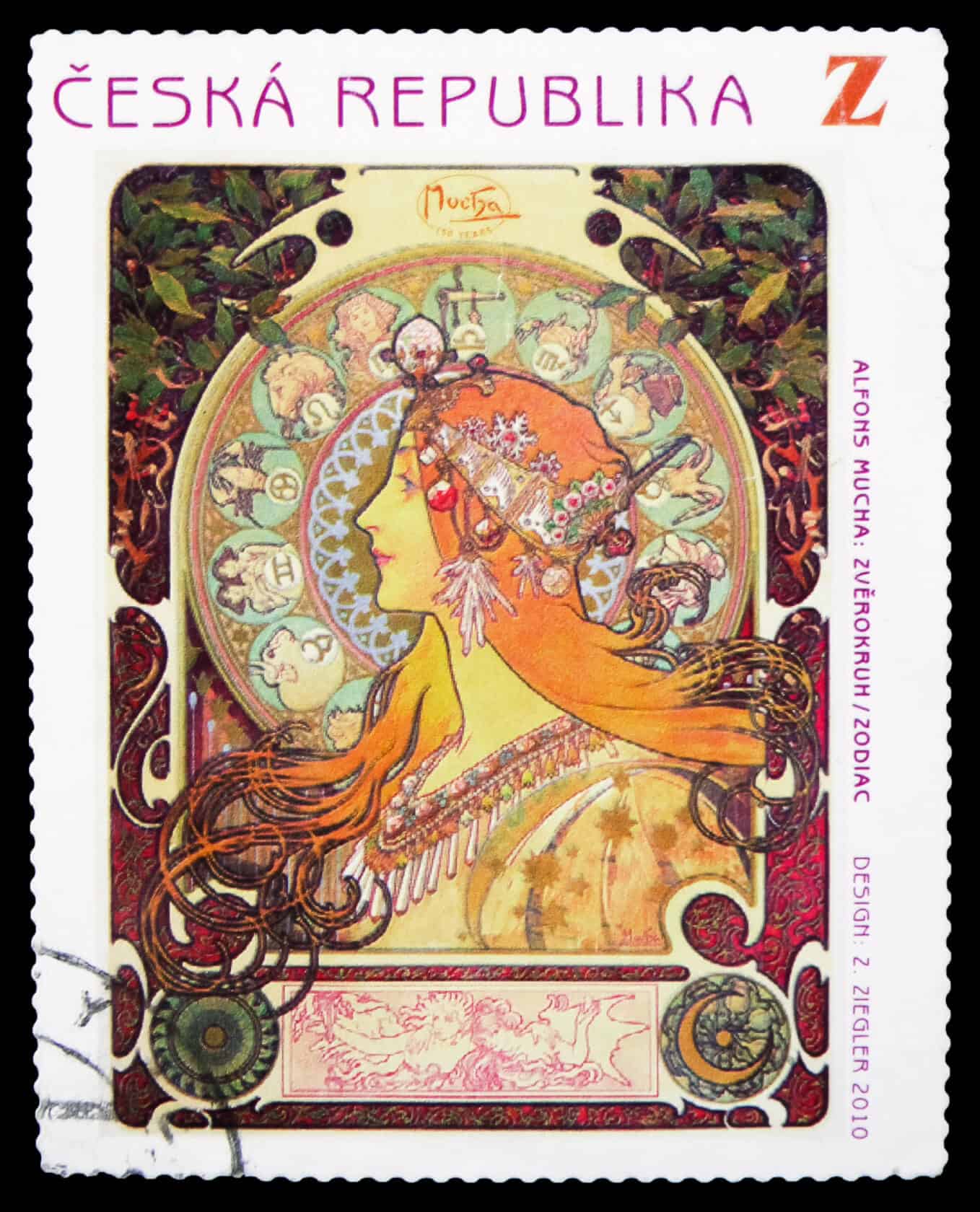

The fin-de-siecle, the end of the 19th century, was the era of evocative shades and seductive compositions. It’s the age of beauty and neoclassicism, but most importantly, it’s the age of Alphonse Mucha.

The Art Nouveau movement first occured in Europe in the 1890s and lasts for a short period of only twenty years. Enough time, it seems, to forever leave a heavy imprint on architecture, design and the cultural scene of the entire continent.

This lavish style, heavily inspired by mythology and folklore, carries its fairytale-esque atmosphere through pastel colors and fantastical iconography. Warm and ethereal, otherworldly and entirely captivating, the modernist works from the Belle Époque continue to inspire both audiences and artists alike more than a hundred years later. From Lautrec to Klimt and Mackintosh to Beardsley, we still admire this glorious period of art history, at whose center lies one of its originator – the unique Alphonse Mucha.

Mucha, the conceptual father of Art Nouveau, is one of the most important European artists, whose influences and remnants we can see even to this day. Born in a small Moravian town in 1860, a region that at the time belonged to the Austrian Empire, this Czech master of the fine arts started his education in Brno, where he was first introduced to baroque.

Having started as a singer and gifted musician, Mucha soon left his promising career in music in order to pursue his true passion – art. He found his first employments designing theatrical scenery and other decorations, but after having been rejected from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague in 1878, his ways swiftly led him to Vienna, the political and cultural capital of the Empire.

There, he continued his work for the theater as an apprentice scenery painter for a Viennese company. He started experimenting with photography and portraiture, spending the rest of his free time exploring the rich world of museums, churches and palaces all around the city. It was in Vienna where he was first introduced to the murals of painter Hans Makart, laying thus the foundation for some of his older and more mature works to come in the future.

After several years in this European capital, he moved to Munich to pursue his education under the patronage of Count Belasi, who took a great interest in his talent. While there is no formal evidence that he was actually enrolled into the Academy of Fine Arts, he did, indeed, spend his time in the company of other Slavic artists he would come to admire. In 1887, however, after governemnt restrictions upon foreign students and residents took hold in the city, Mucha continued forward, finding himself eventually in Paris.

His career finally took off in France in 1894 and, some might say, it did so overnight. Having met his lifelong muse Sarah Bernhardt, Mucha painted a portrait of the actress for the poster of a play which had premiered earlier that year at the Théâtre de la Renaissance on the Boulevard Saint-Martin. Today, his masterwork ’Gismonda’ is considered to be a timeless piece of applied arts and in its time it took Paris by storm.

’Gismonda’ was so beloved in fact, that many French lovers of the fine arts took the posters for the play from public places only so they could get to decorate their homes with it. After a printing of 4000 pieces, this design inspired by miz Bernhardt awarded the then 35 year old Mucha with the title of ’Parisian king of Art Nouveau’. He spent the following six years working with the actress, creating a plethora of illustrations, sketches, theater costumes, jewelry and propaganda material in the meantime.

Having started his own studio, this Czech artist continued to work hard on his illustrations. Once his friend, the famous impressionist Paul Gauguin, came back from Tahiti and joined him, it marked the start of Mucha’s most productive period during which he created the glorious artworks we still remember him by today.

While inspiration came to him from many different angles, Mucha’s trademark semeed to be different portrayals of nymph like women with gorgeous, long and curly hair. His motiefs were always mythological, closely linked to nature itself, always incorporating warm colors, a golden shimmer and floral ornamentation.

His fascination with the four seasons could be seen even in a couple of different series of paintings, in which, between the lines, we can read the great love this artist had for his homeland and Slavic roots. His ’Slav Epic’ series is perhaps among one of his most complex and most personal works, yet he is better known for the masterpieces such as ’Zodiac’, ’Daydream’ and ’Princess Hyacinth.’

With the unexpected explosion of the marketing industry, marking thus the end of the 19th century with a boom, Mucha’s work began to be more and more commercially successfull. Soon, his paintings would become synonymous for brands such as Lefèvre-Utile cookies and Ruinart Père et Fils champagne.

This, however, didn’t agree well with the artist himself. Mucha found this work tiresome and frustrating to the end of his life, leaving him with the feeling that it distracted him from his real art. He created with a fierce conviction that artworks needed to condone a spiritual message and that their only role and purpose was to have a meaning, which completely negated his partaking in a consumerist society.

Mucha met the end of his days during the Second World War. As a Slavic nationalist, with a Jewish heritage, he was one of Gestapo’s biggest targets during the nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia where he was living in the year 1939.

He was one of the first people arrested for questioning and, while he survived that encounter, he had developed a case of pneumonia which eventually took his life in July of the same year. He got to be almost 78 years old and was buried in a cemetary in Prague.

The imaginative and fruitful style of Alphonse Mucha left an entire legacy to Europe’s cultural heritage. His soft and neoclassical figurines surrounded by floral halos around their heads, enriched every city he got to live in. His paintings, posters, illustrations and designs left a lasting impression on entire generations that came after him and will continue to do so to the end of our days. If you ever think of Art Nouveau, you should, in fact, be thinking of Mucha, because without him this movement might not have existed at all.

Editorial credit: Mirt Alexander / Shutterstock.com

Read more about some of Budapest’s most interesting museums.

Support us!

All your donations will be used to pay the magazine’s journalists and to support the ongoing costs of maintaining the site.

Share this post

Interested in co-operating with us?

We are open to co-operation from writers and businesses alike. You can reach us on our email at [email protected]/[email protected] and we will get back to you as quick as we can.