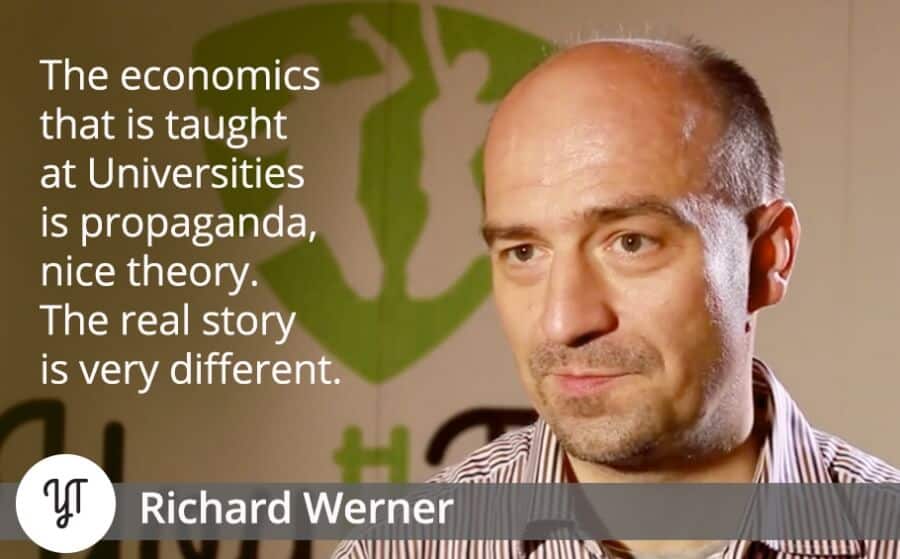

Did you know Central Banks only create three per cent of the money supplied while 97 per cent is created by commercial banks? Would you like to find out what is actually hidden behind banking crises and recessions that have stricken the Eurozone? At the YT Summer School in Hamburg we made the acquaintance of the world’s leading expert on central banks, Professor of International Banking at the University of Southampton (UK) Richard Werner. During “Interview with a guest” session, he pinpointed several key issues that fit into today’s world themes. His speech will be published in two parts; the first one is about modern economy and its true essence.

We were very curious, where does your interest in economy originate from? What kind of person does it take to be writing about economy and becoming a professor in banking?

Well the truth is, I was a student at school, in high school in Southern Germany in Bavaria, in a fairly rural little town and liked writing and decided I was going to be a novelist. But, one thing I realised is that if you want to write something good, it’s fairly deep, and there is a lot of knowledge of people, of countries, of cultures, of how people behave, of problems of people and humanity. And I decided, well, it’s going to be ridiculous if I write a book when I’m 18. So I’ve got to go out and see the world. So I thought I’ll do this “business economics”, whatever it is. I had no idea! It’s going to be international, it’s going to help me to see the world. So I ended up doing my first degree at the London School of Economics, University of London. I was amazed at how abstract this Economics was that they taught, and I wasn’t really learning deep insights from that Economics. Basically, what I found is that there is a bit of an issue with Economics. I realised that the Economics that is taught at University is not the real Economics. It is a whole second economics of how things really work. I spent 12 years in Japan, and there they have a concept, namely that there are always two truths. One is the “Tatemae (建前)”: the official story, the official truth. Then there is the other truth, the “Honne (本音)”, the true self, the real truth, and in Japan it is culturally accepted that, at a formal meeting, this will be Tatemae, this will be the official story. But, after that they would say at dinner for example, “Sorry, today in this formal meeting, of course I had to tell you the official story and of course it is actually quite different. Here’s what’s really happened”. And Japan is criticised a lot for that, particularly by people coming from the West. This is a general lesson: there is always the official story, and there is the true story. So one has to learn to think for one’s self and learn to recognise the true story.

You are the founding director of the Centre for Banking, Finance and Sustainable Development, and you’re involved in an initiative called Local First, a non-profit initiative. Could you explain a little about your concerns about taking part in such activities?

Once I started to study economics, I was a bit dissatisfied with the abstract approaches, and the thing that continued to motivate me was that the majority in this world still lives in poverty. There are many developing countries and they don’t seem to be doing so well. There is a lot of inequality and I wanted to find solutions to that. It turned out that during my time in Japan, I realised that what I’d been taught before was more or less propaganda, developed in the 19th century by the leading economic poet, which was Britain at the time, in order to suit its own needs. It was the biggest manufacturing country in the world, and it needed to open up other markets for its product. So it developed the ‘free trade theory’ which says – open your markets, it’s good. Well, it’s good for Britain! and, in the post war era, the same ideas continued by the ‘Washington Consensus Institutions’ the IMF and the World Bank. You start to realise there’s a lot of this Tatemae going on, and the Honne is quite different and it motivates you do something about it. In Japan I spent a lot of time talking to politicians, I was in touch with all the leading parties. But even when politicians would entirely agree, nothing would ever change. And I started to get pretty frustrated with that, and I found that in the UK it was even harder to get to the politicians. Even when they agreed, nothing would change. So I decided, “forget about politicians, there’s got to be something we can do, people can do” on the ground, bottom up in their local areas. And it’s a long story, and a lot of research behind this, but the conclusion, the key insight is that, it may be something you already know, and especially if you’ve not studied economics, it is all about the money. The money. Who controls, who creates, who allocates the money. Now that’s in the hands of the big banks, the central banks, they play a crucial role there, and there is too much power there, and they’ve abused this in many ways, creating boom-bust cycles, recessions, ensuring that developing countries do not develop so they can be exploited and their resources can be taken and so on. So we have to tackle this by breaking up this concentrated money power, and we can do this by founding small local banks. I have to ask this question, where do you think this money comes from? We all use money, where does it come from?

Audience: Nowhere

Well, that’s one possible answer.

Audience: Central Bank

Audience: Commercial banks can create money by lending money

Money is created by banks! Most people, when you ask them, will say Central Banks, or maybe the Government creates money, and this what we’re being told. But the truth is, Central Banks only create 3% of the money supplied. 97% is created, just as you say, by commercial banks. Banks do this, by what is wrongly called lending because banks are normally shown as to gather deposits and these deposits are being lent out. This is not what banks are doing. When they give a loan, they create new money that didn’t exist before, so they decide how much money to create, who to give to and for what purpose, and that will reshape the economic landscape. I developed a model to explain this and test this Quantity Theory of Credit which works very well. Money is used for GDP, it’s used for non GDP transactions, for asset markets you get asset inflation, and boom bust cycles and banking crises. This is a crucial power that is in the hands of the banks, and these banks are very concentrated large banks working with large industrial groups and the elite. That should be in the hands of the people, and and I realized that in the country where I come from, there is a system where 70% of the banking system in Germany is in the hands of not-for profit community banks. And then you get more democratic capitalism. And also, there’s a principle where big banks lend money to big firms. Who lends to small firms? Small banks. So if you don’t have small banks, like in the UK, where the 5 big banks are 92% of the banking sector, small firms don’t get any money. So we need to create local banks, not-for-profit, controlled by the local community, and that basically decentralises power. It’s like having your own Central Bank, as banks create money. And this is what we’re doing. Local First a community interest company is creating not-for-profit community banks based on the original German model, which is unfortunately under threat from Brussels and from the ECB, they want to dismantle this, too much economic democracy, so they want to destroy them. We’re trying to introduce them in the UK and also other countries.

So the current economic system mainly serves the interests of business elites and ignores the great majority of people?

Well, clearly yes. The system, this can be demonstrated quite easily, is for the benefit of the small minority. It’s a system of extraction, where it’s taken from the majority, and given to the small minority. But, it’s also a clever system because it shouldn’t be too obvious, so this is somewhat hidden, you will identify it, but it’s somewhat hidden. And most of all, there is great propaganda and this is the official economics, to hide this. And one of the control mechanisms, transfer mechanisms is interest.

I am studying economics, so I’m a little bit familiar with these theories. My first question is, after the crisis of 2007/8, there is something wrong with monetary policy. So should we focus more on Fiscal Policy, policies for countries? Is it fiscal policy that determines the potential output, or is there something else that is wrong in our daily life? Secondly, you have huge experience in Japan. If you read Paul Krugman, he writes about the liquidity trap, and he says that Japan is in the trap. I feel that it’s the interest rate that leads to this liquidity trap and it’s not just restricted to Japan but entire world is facing it. So do we have any other alternative to help resolve this problem?

Let me start with the second part, which comes to the fiscal policy question. Paul Krugman says there is liquidity, so you lower interest rates and nothing happens and the economy is not stimulated. Economists are puzzled as to why this is happening. This is because the official theories are wrong. The official theories say you’ve heard this many times, when you lower interest rates, this stimulates the economy. This has never been true. Of course this is repeated a lot in the newspapers by journalists. But this has never been empirically proven, there’s no empirical evidence for this whatsoever, in any country. It’s just a nice theory, nice propaganda. The truth is, interest rates follow growth. If you have more growth, rates are pushed up, if you have less growth, rates come down. That’s a fact, and you can check for yourselves looking at data – this is what most people don’t do. So, they just repeat this misleading story.

So, what is driving growth? If its not interest rates, so what then is it? We’ve said it already actually, it’s the credit created by commercial banks. Because for any transaction you need more money. Growth means there are more transactions this year than last year, that means more money has to change hands. In our system that we have, it’s only possible if the banks create more credit for GDP transactions this year than last year. And if this happens, you’ll get more growth, if not you won’t. So, in order to get to get growth, whether it’s Japan who had 20 years of recession more or less, or Greece, Ireland, Spain, Portugal where they’ve had long recessions, 50% youth unemployment, we clearly want more growth. What do we need? We need more Bank Credit Creation for productive purposes for GDP transactions. Its not happening because the ECB is actually killing banks. Its lowering rates to zero, its buying bonds, what they quite outrageously call Quantitative Easing, that is not how I defined it. therefore lowering long-term interest rates, the Yield Curve is flat. If you’re not familiar with this, don’t worry, it just means that banks can’t make money so they don’t lend. The central bank therefore is bankrupting banks, increasing regulation on banks. Therefore, they have to merge because they can’t handle delivering all those regulations. Most bank staff have to write reports to the ECB day in day out, they can’t go out to their customers anymore and do lending. So they merge, and as a result they don’t lend to smaller firms anymore. I warned that unfortunately, we have to expect the worst of this Central Bank, namely that it will create credit bubbles, banking crises and recessions in the Eurozone. This is of course what it did, starting from the following year, 30% credit growth in Ireland, 40% credit growth in Spain, this is credit, money creation going into property, real estate, and its unsustainable, driving up asset prices. This will bankrupt the bank system and you get a recession. So why are they doing this? Well, why did the bank of Japan do the same thing? It’s always the same game. Creating a bubble in the 80s, bankrupting the economy until they’re highly successful, and then creating a 20 year recession, and the refusing to increase bank credit, but it had a political goal. This is what I said when they cut me off on CNBC, but you can read all the evidence, the eyewitness quotes and the data in the book. The Bank of Japan was under instruction, off the record, from America actually, to destroy the economic system because it was too successful, and the only way to do this is to create a crisis. And the easy way to create a crisis is to get everyone to speculate in asset market property, the banks lend for that. Everyone is making money, they all think this is great. You get a speculator frenzy, it’s a house of cards. It’s not sustainable, the money can never be paid back. You’ll need ever increasing property prices for this to work, and they only rise when banks continue to crave more money. So once that stops, property prices fall, bankruptcies. It’s like this game, Musical Chairs. If we arrange these chairs in the middle, enough for everyone, one chair, music plays, we walk around, we take one chair away. When credit creation sinks, there aren’t enough chairs. Companies have to go bankrupt, borrowers have to go bankrupt, and banks quickly shut down, and then you get a recession. So the bank which I could prove was doing this on purpose, and this came as a bit of a shock to me, that the Central Bank would do this on purpose, and if you hear this for the first time, it probably will sound like a hard story to believe. You have to look at the story which is there in the details. But you will find the same pattern with other central banks. This is the money game that’s being played.

My question is about the GinI coefficient. Now the GinI coefficient has increased dramatically, and it’s really quite worrying, so I was wondering what are the things that we can do to tackle this problem, and more importantly, would you like to elaborate on how to do this?

Basically, where you have countries where you have a concentrated banking system, and you have bank credit creation of course for speculation, financial market transactions, as has been the case in the UK, the US and also periodically as we saw in many European countries, you will increase inequality, because there’s a lot of people in the financial sector that are getting huge salaries but are not producing anything useful. That’s a fact – I’ve worked in the financial sector. The financial sector is basically extracted. It’s like a parasite sucking the lifeblood out of the economy. Of course, this is not the official story, the official story is that it’s helping rather. Well, you think it through (laughs). Well, that increases inequality. So what’s the solution? I think it is, like I said at the beginning, to change the financial system. It’s probably most effective if you don’t try to have a revolution outright. Most people are scared of big changes. You do it step by step, by founding community banks, which are not for profit, there are no bonuses being paid there. They don’t charge customers, they don’t trick customers, all the benefits go back into the community, and you will see countries which have such a system have a lower GinI coefficient. So Sweden, Germany, Japan, they’ve had loads of community banks. they’re also under threat, in the last ten years, they’ve reduced the number of community banks, but that’s historically a key reason for lower inequality. Of course there are other factors, labour markets and so on, but that’s a key fact, because it’s all about the money.

I would like to ask you how you think the situation is going to look like now in regard to the creation of this new Development Bank?

I think its pretty exciting, this development. Effectively this could turn out to be a new monetary system, because the system that we’ve had since 1944, the Bretton Wood system, which is dominated by Washington, it’s a dollar centric system, in fact since the ’70s since the link to gold was cut, and the U.S. defaulted on its gold promise, it became a petrol currency, an oil dollar. So this system serves mostly America and American interests and it’s not really an equal system where all countries have an equal chance, it’s a very one-sided system. Now it seems we have the first step towards a more diverse international money system with alternatives to the dollar. You have Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, this new Shanghai Bank, there is talk about creating a monetary infrastructure alternative to SWIFT, you know, the banking settlement system. Basically countries could settle outside the dollar. Some people have pointed out that whenever a dictator in an oil country was playing ball, it’s OK, because he’s a dictator. But if he starts saying “I’m going to sell this oil for other things than dollars” then suddenly the newspapers will write he’s a bad dictator and the troops would come in and he’d be gone in a very short time period. This may be true or not, but whenever there has been an attempt, to challenge the dollar, there’s been quite a vicious response, so now, if China’s involved, and Russia’s involved in doing this, there is a possibility this could happen; there could be an alternative system so that’s quite exciting.

Read part II of the interview with Prof. Werner on Friday, July 24.

Support us!

All your donations will be used to pay the magazine’s journalists and to support the ongoing costs of maintaining the site.

Share this post

Interested in co-operating with us?

We are open to co-operation from writers and businesses alike. You can reach us on our email at [email protected]/[email protected] and we will get back to you as quick as we can.