In recent months, tragedies at sea have sadly raised everybody’s awareness of the greatest immigration crisis since the Second World War and have cast a bright light upon an ongoing humanitarian calamity in the Middle East. Large numbers of Syrian asylum seekers off the coasts of Southern Europe have awakened debates about the migrant issue and have set in motion a lengthy decision-making process to determine how to address the situation. Meanwhile, countries on the peripheral borders of the EU are still waiting, in the absence of fundamental European reforms, for more precise regulations. Persistent instability at Europe’s southeastern boundaries calls out for realistic solutions, feasible and sustainable plans, and the voice of the EU’s leading Institutions. But what about the young citizens of Europe? They represent the future, and they have the right to raise their voices up, too.

To make an attempt to answer to this with accuracy, we decided to conduct a research project based on a 10 question survey which has been distributed through all the identifiable official European and pan-European youth channels. The collection of the results has been based on reaching 100 samples over a period of 8 full days, trying to achieve as much variety among the respondents as possible (nationality, age, field of studies/work, etc.).

The Survey design: “Refugees and the youth perspective”

The structure of the research has been based on 10 mixed and strategic questions which have aimed at gathering the opinions of young people in general and only a small percentage of youth workers, youth leaders, and youth policy-makers (distributed by age: 18-21, 22-25, 26-30, 30-35, and over 35). The survey has been responded to by 108 people in conformity with the requirements, and the data has been processed on a triple basis: quantitative (according to the graphics created by the system when answering defined questions), qualitative (analyzing those opinions of European youth per area when answering open questions), and transversal (summing up from the general to the specific trends and reported issues and visions).

Countries covered

The young people responding to the survey have come from various European membership areas: 25 European countries (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom); 5 Candidate Countries (Albania, Bosnia i Herzegovina, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey); and 5 Other European countries (Belarus, Moldova, Russia, Switzerland, Ukraine).

Plus another two external groups of non-European young people: 4 Mediterranean countries (Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Jordan); and 2 countries in North America (Canada, United States of America).

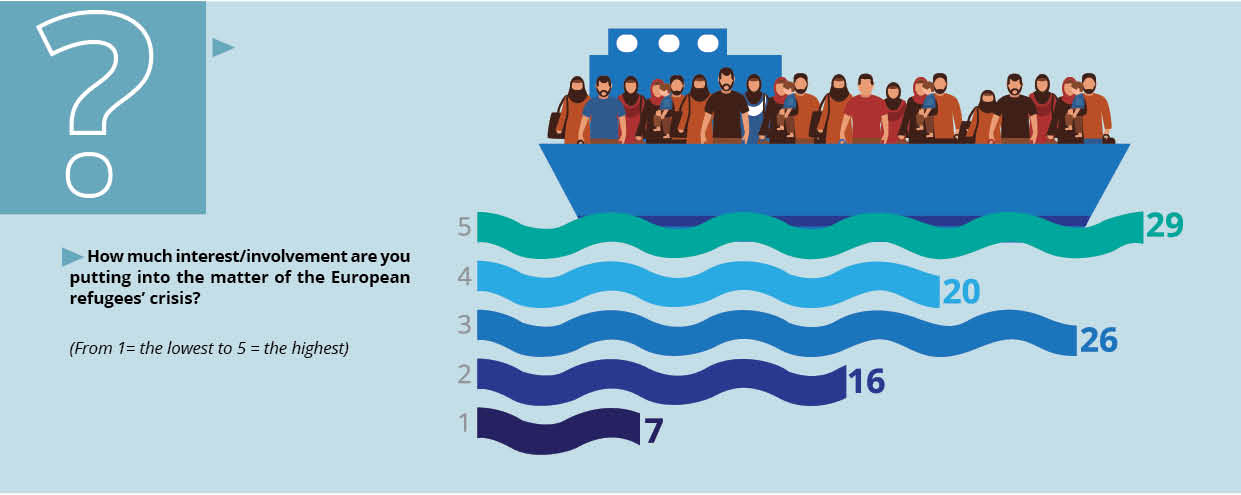

Interest and involvement of youth

If we have a quick look at the data, young Europeans have an involvement in the refugees issues of 3,49 average in a scale of 5,0 as a maximum; more precisely, the most involved ones are aged 25-30 (4,18) followed by the over 35 (on a 7% allowed, the average is 4,72). Younger people from 18 to 25 years old are less focused, and some of them have remarked that two factors underlie their sense of detachment: first, they do not trust the media; and, second, they consider the local and national authorities to lack trustable organizational integrity, especially respecting the issue of guaranteeing safety. Somehow, those factors are discouraging them from following the news actively and plugging into the information process. There is a noticeable fracture between some specific countries and zones: e.g. the Baltic countries are not devoting a lot of energy to this issue, some Northern Europeans are only moderately engaged, while the Balkan states have a quite considerable number of young people and youth workers involved in humanitarian activities; the most committed European youth activists come from Italy, Germany, Austria, France, Greece, Spain, Turkey, Romania and Poland.

Another relevant question which the Survey asked was whether those responding have been or currently are participating in an initiative, event, or activity at the humanitarian and/or social level, and, if yes, which one. Surprisingly, only 63 young adults answered this question, while 37 skipped it; 30 out of 63 are not directly involved, but the majority of the responders noted that they would like to contribute somehow but “unfortunately, it is difficult”. The other 33 young activists all come from European countries and the Balkans; they described the activities they are participating in, and the resulting data disclose an impressive variety of humanitarian actions: from psychological help and support to Red Cross volunteering, from anti-discrimination campaigns to tolerance marches, collection and distribution of packed food, clothes, medicine, and hygiene materials, teaching the national mother tongue to children, online donations and adoptions (through safe international bodies), media involvement from those areas and countries from which the refugees were massively arriving, legal documents support and information, sensitization of European students to the refugees and to the specific Programmes and extra-curricular hours to support integration, the

organizing of official conferences to spread information, preparation to volunteer in the camps where the refugees have been welcomed, realization of interviews and radio shows, advocacy for human rights and emergency status defense, proposals of social integration Programmes, support at refugees’ arrival gates at the main train stations in Austria and Germany, at the harbors in Italy, and in emergency cases in Turkey and Greece.

Youth, the European Institutions, and the national Governments

In the past few weeks, the European Commission contemplated the possibility of allocating quotas of refugees and asylum seekers to each European state for a total amount of 160000 desperate Syrians who have reached the shores of our countries. Fully 100% of the answers, including 74 comments, provide us with a cross section of youth perspectives and expectations, with an apparent undercurrent of sadness about the Institutions and the European bodies. Forty-five percent of the respondents agree with the allocation, 18% strongly agree with the European plan, 8% disagree, another 8% strongly disagree, and again another 8% are indifferent to any European decision and a last 8% consider that this matter is nothing they need to decide about. Only 5% abstained.

It is impressive to note that the majority of those who shared a comment, consider that the allocation proposition from the European Commission cannot be an obligation placed upon the individual European states: the distribution of the refugees should be voluntary and should not be seen as a “forced quota of solidarity”, all should be settled according to the real resources that each country has and can sustain for certain. Also, we received a high number of proposals to organize appropriate support at all levels in the Middle East, as long as young people see that all these matters are growing out of an overflowing wave of violence, terrorism, and poverty. But there are also strong perspectives which are calling for the intervention of the Gulf States to support their “Muslim brothers and sisters”, a high number of respondents considering that US politics are the main cause of the war in Syria and that they should have also a plan for integration and humanitarian support, and, finally, they spoke out for security in Europe and expressed concerns about the possibility of ISIS terrorists infiltrating the EU.

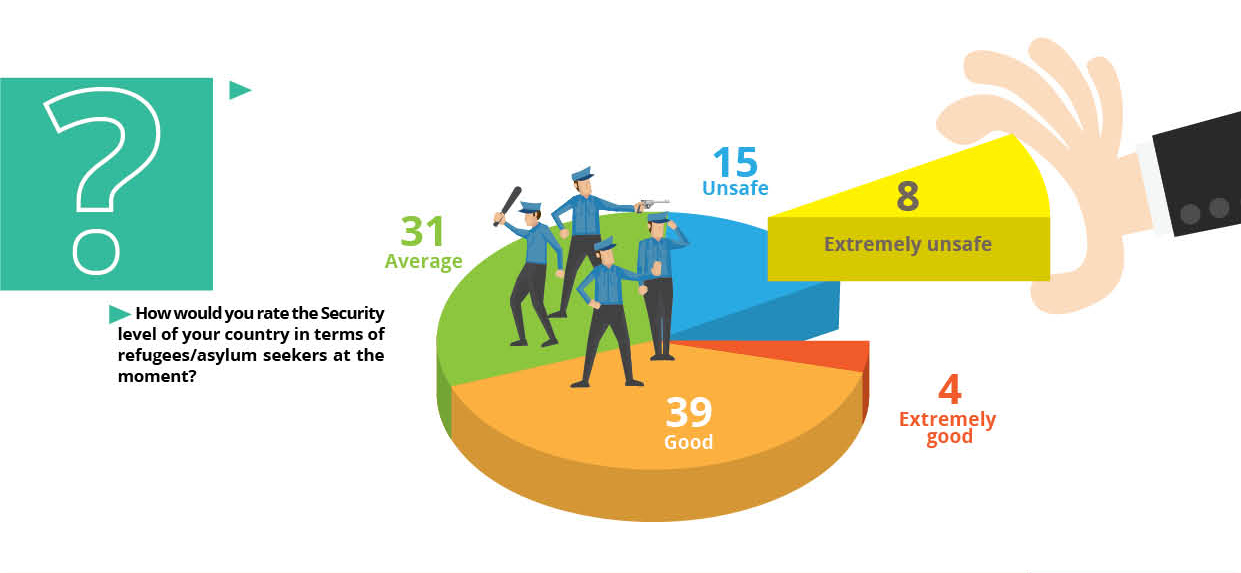

Respecting the last mentioned point, respondents were asked to double rate their countries in two fields: first, the Security level of the European country they live in; second, if they reckon that the same countries have enough resources and basic requirements to face the refugee crisis. Results are in an inverse proportion to what the young people see, and it can sound astonishing: 40,21% of all respondents think that the security level is good, 31,96% consider that the system is just average, 15,46% are unhappy with the Government methods and consider their countries unsafe, 8,25% affirm it is extremely unsafe and only 4,12% express a high level of safety. Geographically speaking, most of the complaints come from the Northern European countries and the Balkans, while Central and Southern Europe has a positive or normal view of the Security systems their Governments have adopted. The fear of crime is somehow hovering at the edge of these European minds, and yet they also denounce the emergence of a trend in which some of the Western countries that are dealing with the refugees’ rebellions at the fences have built up the security systems at their borders while also tolerating illegal trafficking and bribes at the border crossings.

A very complex and controversial situation emerges if we summarize the contrast in attitudes among the European countries in terms of the requirements needed to protect European citizens and guarantee a good, basic welcome to the refugees: thirty-nine percent consider that the European countries have a poor system, 33% think that it is good but can be improved, 20% estimate average methods, 5% support a full “yes, all is working” against 1% who hold that “nothing is working”, while 2% do not know about these matters. The same geographical distribution comes back here with a slight change for the Northern countries which see things working better.

Young people and their open suggestions to their Governments and to European Institutions

When invited to address their concerns to their individual countries, eighty-three percent of young Europeans addressed general tips and suggestions to their Governments and to European Institutions too; the complex schemes they proposed serve to build the groundwork for a safer European environment and a common welfare for citizens and refugees at the same time. The main idea is to create a shared, multilateral task-force based on field-policies for the integration process: the health field (including psychological and mental diseases), social services, law and communitarian duties and rights as European citizens (from the local to the national/international level), education (from kindergarten to Higher Education), efforts to improve employability, specific European funds focused on humanitarian support, a much faster intervention from the political sector and a more coherent bureaucracy (more applicable to Europe), more both national and European humanitarian finances in those hot areas where the refugees are docking, not to create ghettos but to harmonize integration through the construction of proper refugee camps, the realistic allocation of money for those European countries facing and dealing with the emergency in a more direct way, and cooperation between the Authorities and Civil Society (NGOs, Associations, Federations, etc.).

Some pointed remarks arose also from the survey, as for example the lack of intervention on the part of the Gulf countries and the USA to solve the problem, the fact of general unpreparedness for this emergency, and finally one idea which unites a wide number of answers: to sustain a clever and structured plan to stop the war in Syria, to work together to fight extremism and violence, to increase the emphasis on human rights solutions, to develop military strategies to wipe out the aggressions of ISIS in its homeland. But all this is unfortunately seen as falling under the heading of pure “youth utopia”, in fact European young adults have big hopes but not too much trust in concrete actions and in politics.

How to educate those young Syrians who have lost all hope for a fair future?

The last bullet point from our research touched on the matter of the young Syrians who have lost the right to a worthy education and to a fair opportunity for personal and professional development for their future. Eighty-five percent of all respondents answered this question, and their contribution deserves deep reflection; young Europeans really see the Syrian refugees as part of their future, and so as part of the over-all challenge facing European Education.

The proposed solutions to fill the educational gap cover the spectrum from English and local language instruction, opening Alliances for humanitarian kindergartens and studies with free access, to involving Syrian students in cultural training in the country where they have settled, to building a European plan with specific, targeted grants for them, a volunteering and employability plan (part-time) in proportion to their development, free college housing and an off-fees system, creating a meritocratic entrance system (test-based) in case of funding restrictions, agreeing on creative ideas such as “study and hospitality” (European families who could take care of Syrian students for the duration of their studies while staying at their home with Government financial aid), using mobility grants for better inclusion, creating an “emergency student VISA”, and, at least, providing free online education at all levels and in all fields. But meanwhile, a small percentage of young adults expressed skepticism about the veracity and the proper access to our European studies when Syrian students lack basic information and this allows them to be doubtful of successful outcomes.

Again, “the young European utopia” appears, as some of them emphasized on our research form. But, for sure, we have nothing to lose in trying to be “humane humans”, because we still believe in our European values.

This article was originally published in Youth Time print edition, 32nd issue. Click here to check the content of the issue, subscribe here, purchase one issue here.

Support us!

All your donations will be used to pay the magazine’s journalists and to support the ongoing costs of maintaining the site.

Share this post

Interested in co-operating with us?

We are open to co-operation from writers and businesses alike. You can reach us on our email at [email protected]/[email protected] and we will get back to you as quick as we can.