The memoirists highlighted below range from acclaimed writers to former prisoners to humorists to heroes. Their stories are immersing, sad, staggering, and frequently clever. They're straightforward and basic, welcoming you to take in individual lives as you ruminate over your own. They're loaded with life.

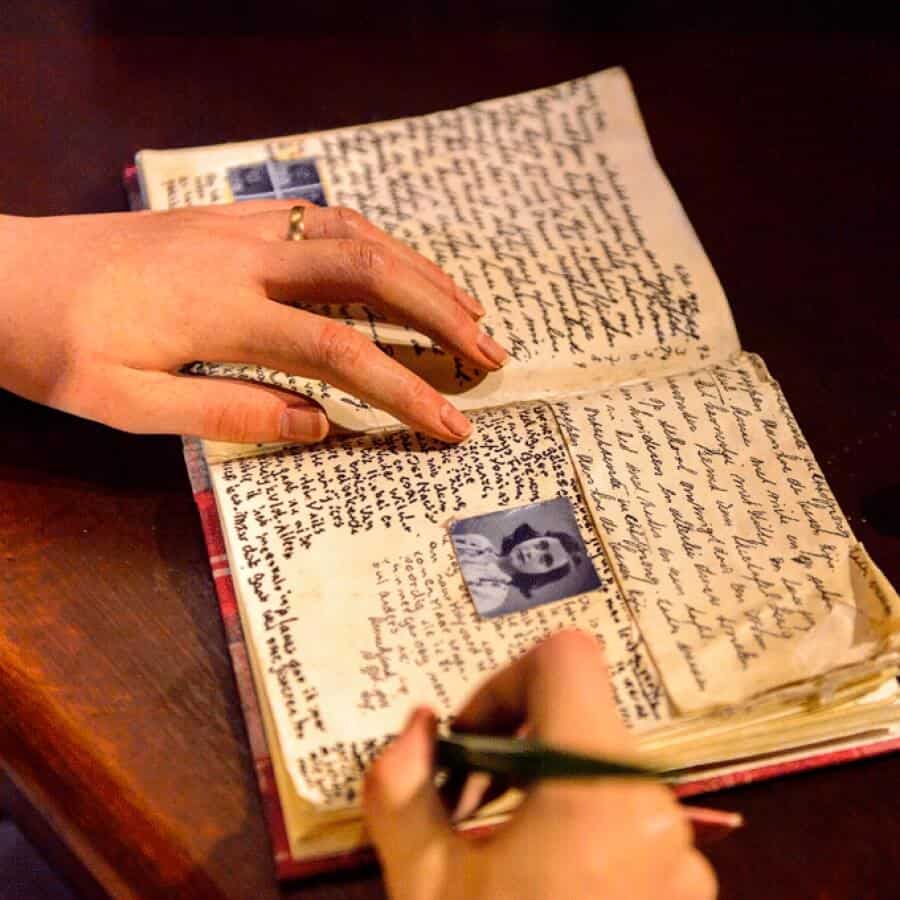

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

In 1942, with the Nazis invading Holland, a thirteen-year-old Jewish teenager and her family fled their home in Amsterdam and went into hiding. For the following two years, until the day when their whereabouts were sold out to the Gestapo, they and another family lived in isolation in the “Mystery Annexe” of an old office building. Cut off from the outside world, they confronted hunger, fatigue, the steady savageries of living in restricted quarters, and the ever-present danger of betrayal and death.

In her journal, Anne Frank recorded striking impressions of her life during this period. By turns mindful, moving, and diverting, her record offers an interesting critique on human fearlessness and frailty and a convincing self-portrayal of a delicate and energetic young woman whose promise was abruptly and appallingly cut short.

“It’s really a wonder that I haven’t dropped all my ideals, because they seem so absurd and impossible to carry out. Yet I keep them, because in spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart.”

The fact of the Holocaust makes reading this journal doubly shocking, given that it is the product of just one person’s energy and experience in the face of catastrophe.

As a 13 year old girl, Anne is grippingly understandable – the way she communicates her feelings and emotions about herself as well as other people’s is astounding. She’s ready to dissect herself in an especially legitimate manner, her capacities, disappointments, and shortcomings.

“I’ve found that there is always some beauty left — in nature, sunshine, freedom, in yourself; these can all help you.”

Anne’s journal ends abruptly in August of 1944, without a conclusion. No more words appear in its pages. Somebody had betrayed Anne and her family to the Nazis, and they were captured and transported to different prison camps. The journal was forgotten and was later found by one of the workplace staff. After being interned in two concentration camps, Anne and her sister Margot were sent to Bergen-Belsen, where they both died. Only Otto Frank (the young girls’ dad) survived.

“Although I’m only fourteen, I know quite well what I want, I know who is right and who is wrong. I have my opinions, my own ideas and principles, and although it may sound pretty mad from an adolescent, I feel more of a person than a child, I feel quite indepedent of anyone.”

The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls

A delicate, moving story of love in a family that, in spite of its significant defects, gave the writer the self-assurance to carve out an effective life on her own terms.

“You should never hate anyone, even your worst enemies. Everyone has something good about them. You have to find the redeeming quality and love the person for that.”

Jeannette Walls grew up with guardians whose goals and willful dissention were their salvation. Rex and Rose Mary Walls had four youngsters. Above all, they lived like wanderers, moving among Southwestern towns, and outdoors in the mountains. Rex was an appealling, splendid man who, when calm, caught his children’s creative energy, showing them material science, topography, or most of all, how to grasp life courageously. Rose Mary, who painted and composed and couldn’t stand the duties of accommodating her family, called herself an “energy fiend.” Cooking a feast that would be expended in fifteen minutes held no interest when she could create an artistic work that might live forever.

“Things usually work out in the end.”

“What if they don’t?”

“That just means you haven’t come to the end yet.”

Through it all, regardless, she cherishes her folks. She recollects her dad as a wise man brimming with fantastical stories, and her mom as an energetic craftsman. It’s fascinating, however, how variously readers have reacted to them.

Typically, a persuasive story makes readers feel they share the storyteller’s point of view. However despite the fact that many can comprehend Walls’s love of her folks, many readers have disdained them for being egotistical and careless, for example, despising them for permitting a three-year-old to use the stove routinely (and cause herself genuine harm).

“Life is a drama full of tragedy and comedy. You should learn to enjoy the comic episodes a little more.”

In any case, this is not feedback. The Glass Castle is a flawlessly composed, enthusiastic perusal, a genuine Bildungsroman, brimming with fascinating stories and characters.

Running with Scissors by Augusten Burroughs

The genuine story of a criminal adolescence where rules were blunt, the Christmas tree remained up all year, Valium was expended like sweets, and if things got dull, an electroshock-treatment machine could give amusement.

“I know exactly how that is. To love somebody who doesn’t deserve it. Because they are all you have. Because any attention is better than no attention. For exactly the same reason, it is sometimes satisfying to cut yourself and bleed. On those gray days where eight in the morning looks no different from noon and nothing has happened and nothing is going to happen and you are washing a glass in the sink and it breaks-accidentally-and punctures your skin. And then there is this shocking red, the brightest thing in the day, so vibrant it buzzes, this blood of yours. That is okay sometimes because at least you know you’re alive.”

Running with Scissors is the genuine story of a kid whose mother (a writer with daydreams of Anne Sexton) gave him away to be raised by her irregular specialist, who looked to some extent like Santa Claus. So at twelve years old, Burroughs wound up in the midst of Victorian filth, living with the specialist’s odd family, and became a close acquaintance with a pedophile who lived in the patio shed. This account of a bandit adolescence where rules were unfathomable is the amusing, nerve-racking, smash hit record of a kid’s survival under the most phenomenal conditions.

“It’s a wonder I’m even alive. Sometimes I think that. I think that I can’t believe I haven’t killed myself. But there’s something in me that just keeps going on. I think it has something to do with tomorrow, that there is always one, and that everything can change when it comes.”

Photo: Shutterstock

Support us!

All your donations will be used to pay the magazine’s journalists and to support the ongoing costs of maintaining the site.

Share this post

Interested in co-operating with us?

We are open to co-operation from writers and businesses alike. You can reach us on our email at [email protected]/[email protected] and we will get back to you as quick as we can.