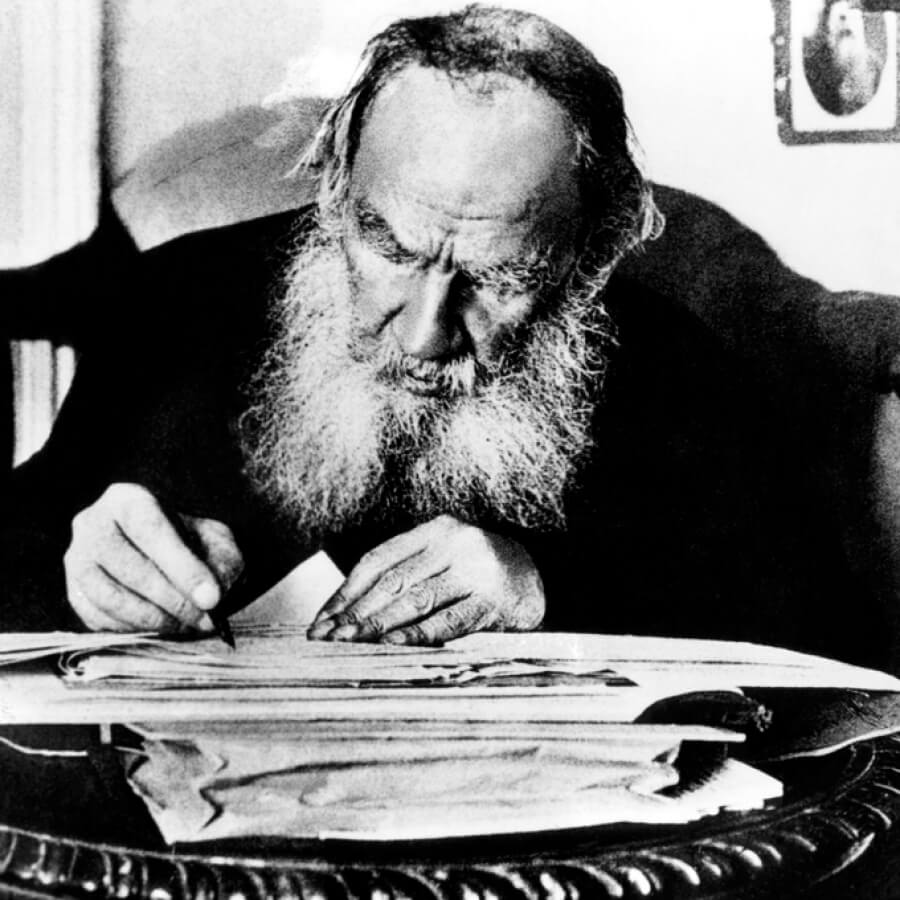

Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, best known as the nineteenth and twentieth century author Leo Tolstoy, is viewed as one of the greatest novelists who ever lived. In this article, we will review three of his first-rate works, from the epic novels that depicted the Russian society in which he grew up to the non-fiction accounts of his spiritual challenges and subsequent reawakening. Enjoy!

Leo Tolstoy Books

Youth Time Magazine has prepared for you this time the list of Leo Tolstoy books that you need to read. Usually, Tolstoy is famous by Anna Karenina, but you will be surprised by how many genius books Leo Tolstoy wrote. Let’s start.

War and Peace

We can know only that we know nothing. And that is the highest degree of human wisdom.

Tolstoy weaves together the lives of his characters against the backdrop of the Napoleonic wars and the French invasion of Russia. The fortunes of the Rostovs and the Bolkonskys, of Pierre, Natasha, and Andrei, are personally associated with the national history that is played out in parallel with their lives.

Tolstoy’s unforgettable characters appear to act and move as though brought together by strings of fate as the novel tenaciously explores choice, destiny, and fortune. However, Tolstoy’s depiction of conjugal relations and his scenes of family life are as honest and powerful as the extraordinary people who bring them to life.

The whole world is divided for me into two parts: one is she, and there is all happiness, hope, light; the other is where she is not, and there is dejection and darkness…

There is no difference in separating Tolstoy’s artwork from his philosophy, just as there’s no way to separate fiction from discussions about history in this novel. With no unifying theme, with no plot or clean ending, War and Peace is an encounter with the style of the radical and with the narrative in history.

Tolstoy groped in the direction of a one-of-a-kind fact – one that would capture the totality of history, and teach human beings how to live with their burdens.

Who am I? What do I live for? What changed when I was born? These existential questions are about the meaning of life, and of free will as opposed to the effect of the outside world. Fictional and historical characters blend naturally inside the narrative, which occasionally turns into a reasoned philosophical digression, exploring the way individual lives affect human progress.

It’s not given to people to judge what’s right or wrong. People have eternally been mistaken and will be mistaken, and in nothing more than in what they consider right and wrong.

Read the online book of Tolstoy here.

The Death of Ivan Ilych

Hailed as a splendid masterpiece about demise and death, The Death of Ivan Ilyich is the story of a cosmopolitan careerist who has by no means given the inevitability of his mortality even a passing nod. But sooner or later, his demise declares itself to him, and to his wonder, he has to stand face-to-face before his own mortality.

The example of a syllogism that he had studied in Kiesewetter’s logic: Caius is a man, men are mortal, therefore Caius is mortal, had throughout his whole life seemed to him right only in relation to Caius, but not to him at all.

How, Tolstoy asks, does this unreflective man confront his most consequential moment of reality? This short novel grew out of a profound spiritual crisis in Tolstoy’s existence, the nine-year-long period following Anna Karenina during which he wrote not a word of fiction.

Morning or night, Friday or Sunday, made no difference, everything was the same: the gnawing, excruciating, incessant pain; that awareness of life irrevocably passing but not yet gone; that dreadful, loathsome death, the only reality, relentlessly closing in on him; and that same endless lie. What did days, weeks, or hours matter?

Either in randomness or nemesis, certain or chanced, nature is unveiled as capricious, ungoverned, and cryptic, and man’s clashes with the boundedness of his banal existence. Ivan faces his impending death in disbelief, then denial swamped with a disconsolation at his disintegration while the world continues to turn.

Always the same. Now a spark of hope flashes up, then a sea of despair rages, and always pain; always pain, always despair, and always the same. When alone, he had a dreadful and distressing desire to call someone, but he knew beforehand that with others present it would be still worse.

Read the online free book here.

Resurrection

Resurrection is the last of Tolstoy’s great novels. It tells the story of a nobleman’s attempt to redeem the suffering his philandering has inflicted on a woman who ends up a prisoner in Siberia. Tolstoy’s imaginative prescience of redemption, completed with loving forgiveness and condemnation of violence, is the theme that dominates the novel. An intimate tale of guilt, anger, and forgiveness, Resurrection describes the social life of Russia at the end of the nineteenth century, reflecting its writer’s outrage at the social injustices that he observed where he lived.

“The whole trouble lies in that people think that there are conditions excluding the necessity of love in their intercourse with man, but such conditions do not exist. Things may be treated without love; one may chop wood, make bricks, forge iron without love, but one can no more deal with people without love than one can handle bees without care.”

At half the length of War and Peace, Tolstoy’s Resurrection is every bit as epic, and through most of its length comes across as his most controversial novel, which seems to have robust political and religious implications alongside the narrative in the story.

One of Tolstoy’s later novels, written during the rule of Tsar Nicholas II and an empire which repressed all political opposition, Resurrection starts out as a court drama but quickly draws us into a hugely profound narrative of an unjust cauldron of crooked legislation, poverty, and wealth at each and every end of the spectrum, and one man’s crusade of redemption for a lifestyle lived where he makes use of his exaggerated importance in society to take advantage of others.

It was clear that everything considered important and good was insignificant and repulsive, and that all this glamour and luxury hid the old well-known crimes, which not only remained unpunished but were adorned with all the splendor men can devise.

Read the online book here.

Photo: Shutterstock

Find out more here:

Support us!

All your donations will be used to pay the magazine’s journalists and to support the ongoing costs of maintaining the site.

Share this post

Interested in co-operating with us?

We are open to co-operation from writers and businesses alike. You can reach us on our email at [email protected]/[email protected] and we will get back to you as quick as we can.