The omnipresent sign # conquered social the media; spread to the advertising sphere, and started haunting everyday language. What psychological need urges us to overuse it? How does the new hash-language shape our thinking? An inquiry into this recent #phenomenon takes us to ancient Greek myths and primitive ape-men.

This year, BBC Radio 2 repeated its traditional short story competition for kids, getting 120,421 texts that were literally crowded with hashtags. The actual winner of the competition was thus the sign #, which got the title “children’s word of the year”. The success of this text feature even inspired a group of enthusiasts to propose a special keyboard with one single button: #. The device, while connected to a computer through USB, was supposed to facilitate writing hashtags. Meanwhile, dozens of online manuals advise how to use hashtags efficiently. However, only a few address the question why to use them at all.

Hashguage of Inclusion

Most of those manuals see the hashtag as a way to emphasize a word or a phrase and connect the content with other similar inputs. The following example illustrates useful ways to assess the suitability of a hashtag for emphasis. Take the sentence: “He told her that he loved her”. Try to place the word “only” in different positions within the sentence and watch how significantly the meaning changes. Now do the same exercise with a hashtag. Does it feel the same as if using the word “only”? Not at all. Instead, when reading “He told her that he #loved her”, your head immediately recalls all the connotations and implications of the word “love”. Similarly, when seeing “…#he loved her…” all the images of a young male lover will automatically pop up in your mind. A hashtag has much more to do with inclusion and connection than with emphasis. We write a hashtag to link our comment or picture to similar content provided by someone else. We desire to be connected, to belong to a certain group and to be defined, understood, and appreciated as such by everybody else who is, for example, #happy or #sad. “Hashguage” is a language of rich context and scarce actual content.

Back to the linguistic future

If the message “He told her that he loved her” circulated through social media, it would be in a rather different form. Something like: “Finally! #confession #heandshe #love # happiness”. It is no coincidence that hashguage omits or marginalizes verbs. Verbs are basic carriers of meaning. In the form of thoughts they flow deep in our subconscious minds. When we speak, they jump up to the surface of our full consciousness and pick nouns, prepositions, adjectives and other words to describe what we want to say – what happened or should happen. However, in the world of online media, everything is immediately visible from images or videos and known from the news. Everybody is supposed to know or see what happened. Consequently, verbs are no longer required. The only thing we need is quickly to choose something already described, and share that we adhere to it by hashtag. #Noproblem.

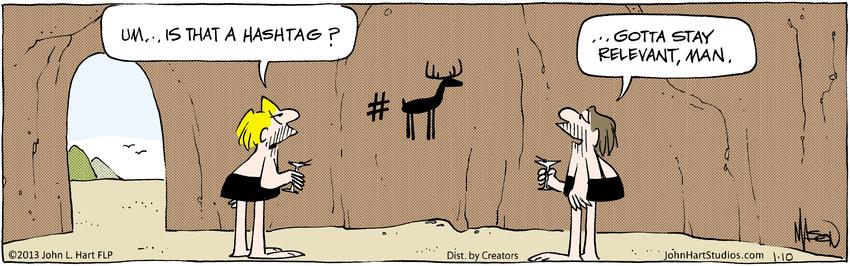

The absence of verbs creates constructions similar to the primitive language of ape-men. By spending most of their time together, ancient tribes shared most of the communication context. Therefore it was entirely sufficient to communicate without verbs: #tiger #danger #fear #escape #sabre-toothed.

Rise of Simulacra

Hash-tagged words and phrases establish artificial blocks of pre-defined meaning. For example, there is no “happiness” that you could feel individually and perceive in myriads of different degrees of intensity. There is just standard #happiness that you have to subscribe to. The desire to be “shared and included” walks hand in hand with the wish to be appreciated and honoured. A lot of social media users therefore carefully cherry-pick the pieces of reality that contribute to the right image. #goodreputation #likesrequested #self-promo.

In 1981 Jean Baudrillard described a theory of simulacrum. He claimed that a simulacrum is a a copy without an original, in other words a situation in which the reality disappears and is replaced by the signs of the reality: “The real is produced from miniaturized cells, matrices, and memory banks, models of control – and it can be reproduced an indefinite number of times from these.” Thus, Baudrillard actually predicted the impact of social media. There is nothing like a #perfectholiday or a #perfectfamily. There are only signs – pictures, statuses, videos – pretending such holiday or such family to others online, signs that are carefully uploaded online and proclaimed to be reality, which they only simulate.

The Myth of Narcissus

The story of the hashtag calls to mind the Greek myth about Narcissus. Narcissus was an extremely handsome young man. Due to his perfect appearance, he ignored all those who loved him, including the fairy, Echo. Once, as he was walking alongside a pond, he saw his own reflection on the water’s surface. He immediately fell in love with himself and could not stop staring at his own face in the pond. Fascinated by his own beauty, he gazed till his death.

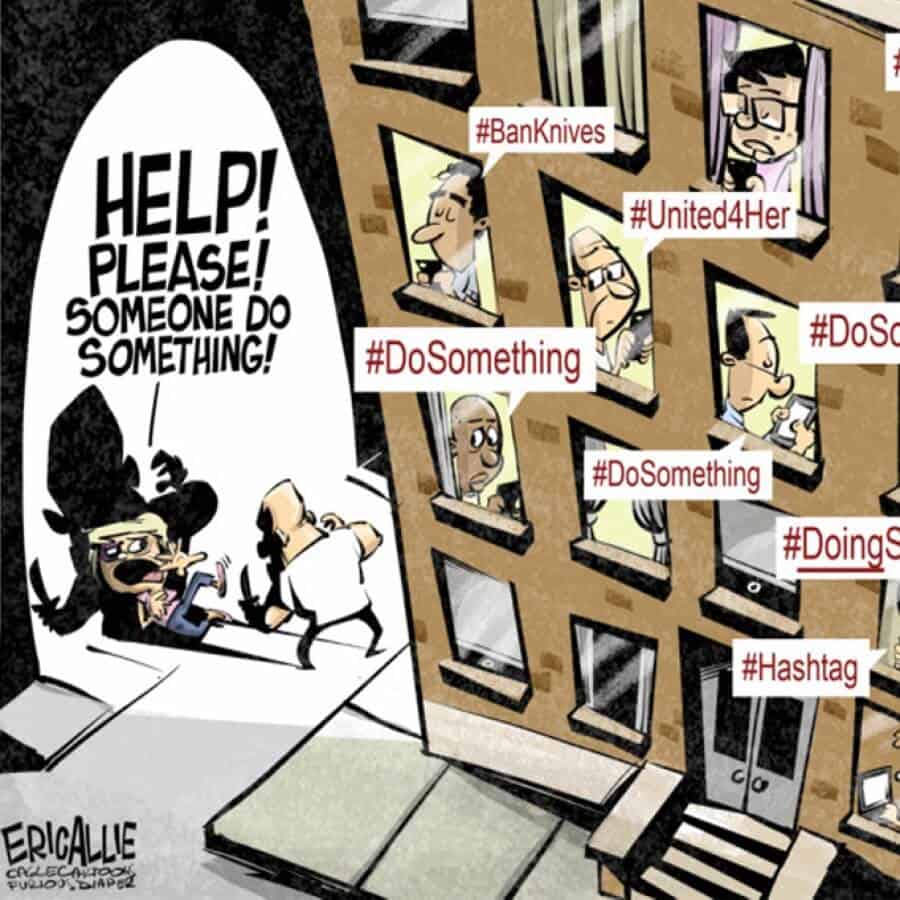

The hashtag could be analyzed as a sort of a pond which mirrors the face of society, its #feelings, #opinions, #lovelydays, #bestdinners, #perfectmornings and #superfriends. While passionately admiring those pre-defined images of itself, society becomes blind like Narcissus. Therefore hashtags may be useful tools for scientific discussion or crisis communication during disasters. Under most circumstances, however, we should use them moderately.

Support us!

All your donations will be used to pay the magazine’s journalists and to support the ongoing costs of maintaining the site.

Share this post

Interested in co-operating with us?

We are open to co-operation from writers and businesses alike. You can reach us on our email at [email protected]/[email protected] and we will get back to you as quick as we can.